The Prohibition Pitfalls of Democrats’ New “Tech Temperance”

Why cultural leadership, not crackdowns, may be Democrats’ strongest tool on tech

Something interesting is happening inside the Democratic Party. It’s also familiar.

Ezra Klein predicted that “the next really successful Democrat…is going to be oppositional” to the tech industry. Rahm Emanuel is urging the United States to follow Australia’s lead and restrict social media for kids under 16. MSNBC host Chris Hayes has been raising alarms about algorithmic design. Rep. Jake Auchincloss is developing an agenda against what he calls “digital dopamine.”

As Lauren Egan recently noted in The Bulwark, some Democratic leaders see political opportunity in raising concerns about the effects of technology, social media, and AI — particularly on families and kids.

Tech writer Max Read has given this trend a memorable name: “platform temperance.” It’s an agenda of “restriction, restraint, and regulation” rooted in concerns about public health and general welfare amid rapid technological change.

But unlike the antitrust obsessions of the Biden era, this new Democratic approach isn’t primarily focused on corporate power. Instead, it’s animated by a broader concern about moral and social corrosion, enabled by unfettered technology.

Echoes of the 1990s

This moment echoes an earlier chapter in Democratic politics. In the 1990s, Second Lady Tipper Gore and Senator Joe Lieberman pushed the entertainment industry toward voluntary content labeling that helped parents understand what their kids were consuming.

I worked for Senator Lieberman and saw firsthand how those efforts broadened his appeal. By addressing family concerns while avoiding heavy-handed regulation, Lieberman’s criticism of violent and sexual entertainment helped him be seen as “a different kind of Democrat.”

As Democrats explore today’s version of technology temperance, that history offers both inspiration and caution. Temperance movements tend to succeed when they reshape norms, and struggle when they drift toward prohibition.

I’m a proud Democrat. I want the party to widen its tent, reconnect with average voters, and rebuild a durable governing majority. I’m also excited by the range of ideas Democrats are offering to refresh and challenge ourselves.

At the same time, I’m a technology optimist. That makes me cautious about solutions that risk turning Democrats away from innovation and toward fear of it. I watched the Biden administration’s hostility toward tech erode Democrats’ long-standing advantage as the party of innovation.

So my assessment is twofold: I find much to admire in this new technology temperance moment. And I worry about what happens if we take it too far.

What This Movement Gets Right

First, Democratic leaders are responding to real concerns. Auchincloss points to suburban parents worried about screen habits. Hayes, Emanuel, and Klein are responding to similar conversations. These anxieties are showing up in kitchens, carpools, and school meetings across the country.

Second, the movement is strongest when it focuses on kids. Jonathan Haidt’s work on the crisis of adolescence has resonated because it reflects what many parents are already seeing. His “four new norms” — no smartphones before high school, no social media before 16, phone-free schools, and more outdoor independence — provide a framework many families and communities find useful. It’s striking how quickly school phone bans have spread at the state and local level; this is one of the clearest examples of regulation aligning with widely shared intuition.

Third, it’s healthy for Democrats to talk more openly about the texture of family life. Our party often focuses on the countless norms broken by Donald Trump rather than the daily realities parents actually navigate: screen time, attention spans, mental health, and childhood independence. Addressing those concerns helps reconnect Democrats with families.

History also shows that the bully pulpit matters. Many people forget that video game ratings and explicit lyric labels emerged because of pressure from Lieberman and Gore, not because Congress passed sweeping laws.

Finally, this moment moves Democrats beyond a narrow Biden-era antitrust fixation. Breaking up companies doesn’t address compulsive scrolling, collapsing attention spans, or the decline of unstructured play. When Klein recently called antitrust law “inadequate” to address tech’s cultural effects, the antitrust brigade reacted defensively — a sign they’ve spent too long treating competition policy as a cure-all. Technology temperance is about family life and norms, not corporate structure.

Where I Worry We Could Go Too Far

Still, the risks are real.

Democrats already struggle with being seen as the “HR department of America,” well-meaning but scolding. And news-obsessed politicians and journalists glued to their own phones may not be the most credible messengers telling teens to unplug. Young people have strong hypocrisy detectors.

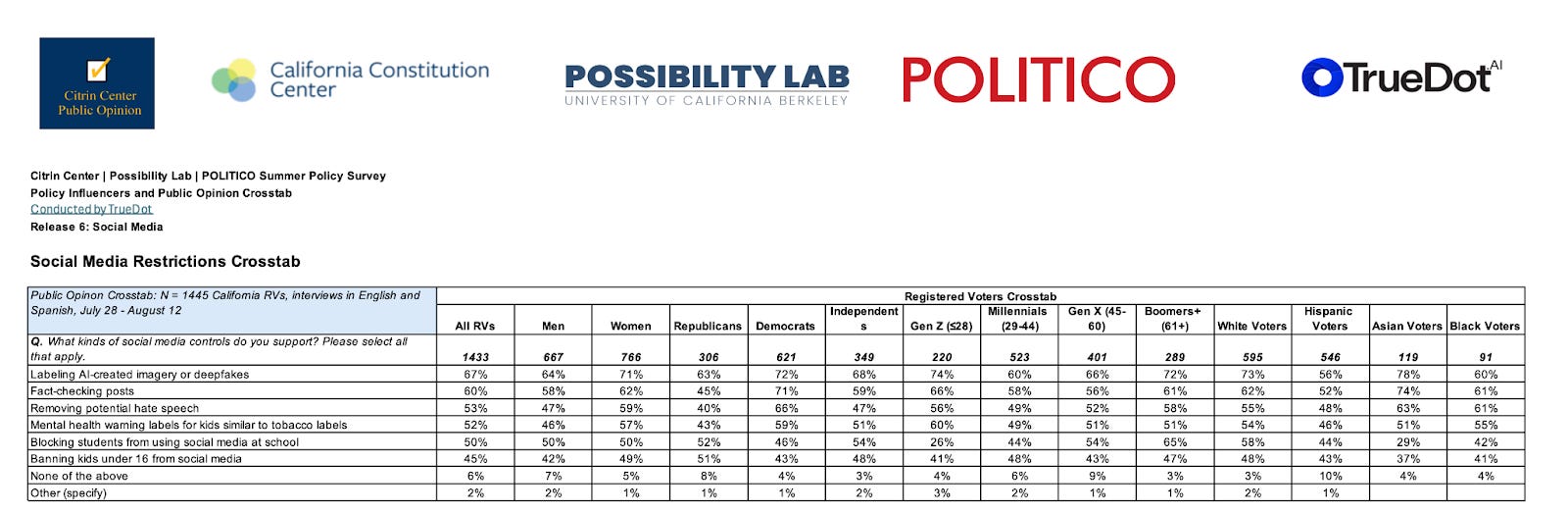

Another concern is coalition politics. Technology temperance may resonate most strongly with voters who Democrats already dominate: white, college-educated, suburban women. A recent Citrin/Politico poll found that nonwhite voters, men, and Gen Z were notably less supportive of banning social media for kids under 16.

For many working-class voters, young men, and Black and Hispanic communities, digital platforms are tools for connection, learning, and economic mobility. Low-income and minority teens report higher internet use than their wealthier and white peers. Could tech temperance be like college loan forgiveness - a myopic concern of our college-educated base, rather than something appealing to the voters we need to win back?

Enforcement is another problem. Australia’s under-16 ban was immediately met with teens explaining how to bypass it using VPNs. In the U.S., many parents already help their kids lie about their age online, a sign that the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) doesn’t align with everyday family behavior. When law moves faster than culture, people simply route around it.

Some proposals also feel mismatched to their goals. Blue state legislators passing new teen warning labels on social media have compared scrolling to smoking. But speech isn’t a toxin, and these labels risk becoming as annoying and ineffectual as Europe’s hated cookie banners. Likewise, proposals to “tax social media ad revenue” as a response to digital vice wouldn’t meaningfully alter how people use these platforms, suggesting more symbolic punishment of companies than serious attempts to change user behavior.

There’s also a developmental concern. Shielding teens from digital environments may leave them unprepared for the world they’ll inherit. Digital fluency — content creation, collaboration tools, media literacy — is increasingly essential. Surveys show that teens want guidance on how to use technology well, not blanket bans. As Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro recently put it, there’s a difference between protecting teens in the digital world and trying to protect them from it.

Finally, there are legal and privacy constraints. Age-verification mandates require collecting more data from both adults and minors, a tradeoff many families dislike. And courts have repeatedly struck down laws restricting access to lawful content, even for minors. However frustrating that may be for policymakers, it’s constitutional reality.

The Risks of Prohibition

Even Jonathan Haidt is cautious about broad regulation. His work emphasizes norms over laws — and norms can be powerful. When I was a kid, I watched unlimited TV. My own kids now have tightly capped screen time. No law made that happen; culture did.

The historical temperance analogy matters here. The original temperance movement successfully reshaped social norms around drinking. But when it escalated to Prohibition, it collided with public resistance and enforcement failure. Temperance endured; Prohibition collapsed.

That’s the lesson for digital policy: norms often succeed where laws fail.

A Better Path Forward

Modern temperance works best through culture, not coercion. Today’s alcohol moderation — Dry January, mocktails, wellness culture — spread without government bans. As Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein showed, nudges usually outperform prohibitions.

Lieberman and Gore didn’t pass sweeping legislation; they nudged industries. Today’s parents already have more tools than ever — from Apple and Google’s controls to apps like Life360 and Qustodio — a sharp contrast to my own childhood in the 1980s, when unlimited television was the norm and no law, but culture, ultimately changed that.

As Shapiro noted, lawmakers should work with industry to encourage investment in tech literacy and education for both children and adults. This sort of investment can give parents a lot more familiarity with the technology their children are exposed to, while helping kids get ready for the future.

Democrats can also learn from Barack Obama. He didn’t lecture people about family life; he modeled it. Imagine a prominent Democratic leader saying: “I don’t support more government intrusion, but in our family we’re waiting until 13 for phones and 16 for social media.” Politicians often underestimate the power of example.

This connects to what Derek Thompson calls “touch grass populism” — encouraging real-world connection over algorithmic loops. Democrats should decide whether they want to emphasize the virtues of balance or the villains of technology.

There are real problems with tech, and accountability matters. But modeling healthy habits may change behavior more effectively than blamestorming. Will Democrats pursue the digital equivalent of Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move — or something closer to RFK’s new vaccine schedule?

Temperance built a healthier drinking culture; Prohibition built speakeasies. Democrats should remember the difference as we decide whether to lead technology’s next chapter, or try to ban it.