How Elizabeth Warren Scared the Biden Administration Into Not Meeting with Tech Leaders

When California Governor Gavin Newsom sent prepaid “burner” cell phones to roughly 100 top executives of California-headquartered companies, he was not simply distributing novelty gifts.

Each phone came pre-programmed with Newsom’s number and included a handwritten note reading, “If you ever need anything, I’m a phone call away.” The message was unmistakable. The state’s technology and business leaders could reach the highest levels of state government whenever necessary. The Governor was open to learning about the technology being invented in his state, the 5th largest economy on the planet.

In the Biden Administration, the opposite dynamic took hold across the federal government. In the absence of a clear directive from senior leaders about the value of meeting with tech industry leaders, Administration staffers picked up signals to adopt Senator Elizabeth Warren’s anti-meeting posture.

Senior officials became hesitant to meet with key technology executives, cautious about how such meetings might appear, and reluctant to treat engagement with innovators as a strategic — even intellectual — necessity. Even hearing from the private sector, let alone collaborating with them, often became seen as a reputational risk instead of a governance advantage.

Contrast that with the approach of the Trump Administration. Many company leaders have deep reservations about the President’s policies from immigration to tariffs, but heap praise on the relative ease with which they can engage Cabinet Secretaries, senior staff, or Trump himself. Biden staff’s lack of access to tech leaders insulated them from critical input about innovation and the state of business.

A Government Without a Tech Bridge

The Obama Administration recognized early that effective governance required technical fluency. It created the role of U.S. Chief Technology Officer (CTO) to serve as a formal bridge between policymakers and technologists, consciously staffed up the economic offices and agencies responsible for guiding technology policy, and often maintained an “open-door” policy that ensured innovators were heard — with a clear, mutual understanding that taking a meeting had no bearing on whether particular advice would be followed or a particular policy outcome would be adopted.

By contrast, the Biden Administration never filled the CTO role at all. No single person was empowered to convene industry conversations or coordinate cross-agency technology strategy.

When I spoke with companies trying to engage with White House leadership, the lack of a consistent point of contact was a constant frustration. The person identified as the “tech lead” was different from conversation to conversation and the lack of interaction was the most common refrain. To a great degree, CEOs viewed Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo as their best contact, but she wasn’t part of Biden’s inner circle.

Junior staff looked to senior staff for guidance. But no one senior in the Biden White House signaled clearly that meeting with the nation’s most innovative companies was a priority.

Without that signal, the administration’s engagement with Silicon Valley defaulted to ambivalence or caution. Officials began to treat outreach as something that had to be managed carefully instead of pursued strategically. I saw this same mindset firsthand during my service as a Biden Administration appointee at the Department of Defense.

Fear of Capture, Fear of Contact

In the absence of a clear signal, many staffers ended up adopting the posture of Senator Elizabeth Warren, who had great influence over Biden Administration staffing and procedures.

Senator Warren’s view, which was reflected in her Senate office as well as Biden agencies like the FTC and SEC staffed by her allies, was that even meeting with industry leaders was inherently corrupting, and should be avoided. Administration officials could not be trusted to hear from the people who they may regulate or provide with government contracts and still exercise their best judgment about what is best for the country.

Senator Warren enforced this view through bullying Biden Administration officials through the media and third party groups. Her allies at the Revolving Door Project and American Prospect published a report in November 2022 noting that Raimondo met with an average of one CEO per day, which was of course part of Raimondo’s job.

In March 2023, Senator Warren sent letters to Secretary Raimondo and U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai warning that Big Tech had too much influence on digital trade rules. Senator Warren’s letters and report referenced emails and meetings listed on public calendars as evidence of undue influence.

“Big Tech has too much influence on policymaking,” Warren wrote, accusing the administration of “outsourcing digital trade policy to corporate insiders.”

— Sen. Warren Oversight Report, March 2023

Many staffers within the administration took Warren’s warning as a reason to disengage entirely. Rather than developing transparent and balanced ways to talk with industry they simply stopped having those conversations. Avoiding contact became the easiest way to avoid criticism.

The result was paradoxical. In trying to guard against undue influence, the administration deprived itself of the expertise it needed to make informed decisions. It was the exact opposite of Governor Newsom’s burner phones to CEOs.

This disengagement was not anecdotal.

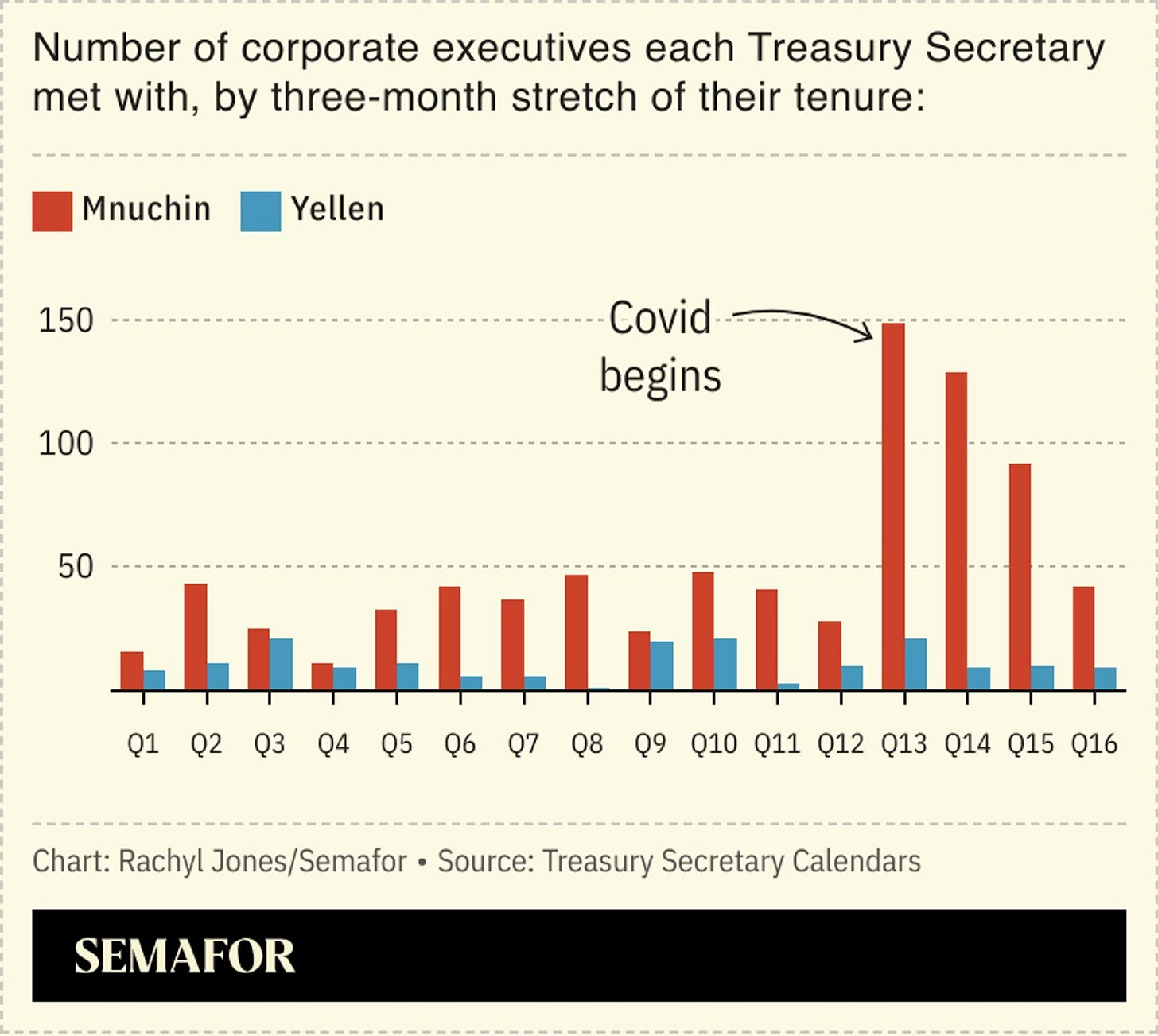

According to a Semafor analysis from January 2025, senior Biden officials took far fewer meetings with industry leaders than their Trump Administration predecessors. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, for example, logged significantly fewer formal meetings with business executives than Steven Mnuchin, who met with corporate contacts roughly every other day.

Across agencies, Semafor found that “when corporate America called, the Biden Administration often didn’t pick up the phone.” The data underscored how a deliberate distance from industry became a defining feature of the administration’s governing style.

What I Saw at the Department of Defense

Inside the Pentagon, even for those of us who wanted to engage, the culture often worked against us. During my tenure as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space and Missile Defense Policy, I made industry engagement a priority. After meeting with SpaceX, my team made sure to schedule additional meetings with Blue Origin and United Launch Alliance (ULA). Broad engagement was generally good policy, but the fear of appearing to play favorites, which I was regularly reminded of from colleagues, could easily have a chilling effect for every official not willing to make time for a full slate of competitor meetings every time they engaged with a company.

Some Biden officials decided it simply was not worth the risk and stopped meeting with industry altogether. If policy officials like me felt that pressure, those with acquisition authority faced even greater scrutiny.

The pace of change in commercial space, satellite networking, and missile tracking was astonishing. For the Department of Defense to stay ahead, we needed to understand those innovations and partner where appropriate. Often the only place I could get the information was from the companies themselves. The developmental programs were proprietary and often classified. To rely on academia or publicly-available information would have left my team in the dark about the critical leading edge technologies necessary to keep our country safe.

At the Pentagon, I was fortunate that my leadership supported this engagement at my level. Earlier in the Biden Administration, I advised Deputy Secretary Kathleen Hicks, who was committed to getting the most from America’s commercial tech sector. She made trips to Silicon Valley to understand the emerging ecosystem and to discuss the Replicator Initiative, which focused on rapidly adopting and scaling new technologies. She recognized that commercial innovation would be vital to national security. However, her portfolio focused largely on internal management and budgeting rather than external outreach.

Secretary Lloyd Austin, who often met with traditional defense contractors and military leaders, did not visit the Pentagon’s Silicon Valley-based hub, the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), until December 2024, well after President Trump had been elected for his second term. By that time, many in the technology community had stopped expecting meaningful outreach from the most senior levels at DoD.

While there were inspiring exceptions across DoD and the administration as a whole, those of us pushing for greater engagement faced the same pattern: caution over engagement. The fear of looking too close to industry caused programs to slow unnecessarily. Innovation often stalled not because of lack of interest, but because too many in the Biden Administration bought into the argument that meeting with industry was corrupt or that they were not willing to be accused of having their judgement swayed from meeting with key industry leaders.

When Fear Replaces Strategy

The irony is that this posture satisfied no one. Powerful Democrats on the Hill and outside of government continued to demand tougher regulation of Big Tech and suggest that the administration was too cozy with industry, while many technology leaders concluded that Washington neither understood their work nor valued collaboration.

Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, co-founder of Andreessen Horowitz, has publicly discussed the difficulty of getting time with senior Biden Administration officials, noting that “no one in the White House wanted to meet” and that requests for senior-level conversations went unanswered.

The consequences of this isolation were both political and policy-related. Without access to senior officials, technology executives lost opportunities to share firsthand expertise that could have shaped smarter regulation, national-security partnerships, and digital infrastructure programs.

The Biden Administration also lost the ability to persuade and influence the tech community. Federal rules and regulations are in many cases a blunt instrument, when a signal for what the government would like to see or what is in the best interests of Americans can help shape investment and policy decisions simply by communicating it in a meeting.

Politically, the Democratic Party lost credibility among innovators and investors who once viewed it as the natural home for forward-looking ideas. The lack of dialogue made it easier for critics to paint Democrats as anti-innovation and indifferent to the industries driving America’s growth.