How Private Sector Experience Helped The CHIPS Act Succeed

The CHIPS and Science Act is one of the most significant U.S. industrial policy initiatives in recent memory – a $39 billion bet on restoring domestic semiconductor manufacturing and authorizing up to $200 billion aimed at boosting U.S. scientific research and innovation.

And it succeeded by tapping private sector veterans, including from the tech industry, to implement the law – over the objections of Elizabeth Warren.

CHIPS Act Origins

This bipartisan law was driven by national security concerns, aiming to reduce reliance on foreign chip sources (especially Taiwan) and bolster America’s tech edge. This rationale was especially important to us at the Department of Defense as we considered vulnerabilities and challenges associated with a potential Chinese invasion and occupation of Taiwan.

As Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo put it:

“One of the Biden-Harris Administration’s top priorities – made possible by the CHIPS and Science Act – is to expand the technological leadership of the U.S. and our allies and partners. These guardrails will protect our national security and help the United States stay ahead for decades to come. CHIPS for America is fundamentally a national security initiative and these guardrails will help ensure companies receiving U.S. Government funds do not undermine our national security as we continue to coordinate with our allies and partners to strengthen global supply chains and enhance our collective security.”

Advanced microchips power everything from smartphones to F-35 jets, and U.S. policymakers feared that offshoring this supply left the country vulnerable. Congress authorized tens of billions to incentivize new U.S. chip fabs and research, historic investments that rank among the highest-profile industrial policies in decades.

The stakes for successful implementation of the CHIPS Act were very high: semiconductors have been called the “lifeblood” of modern technology, serving as the engine driving much of the US economy and underpinning our national security.

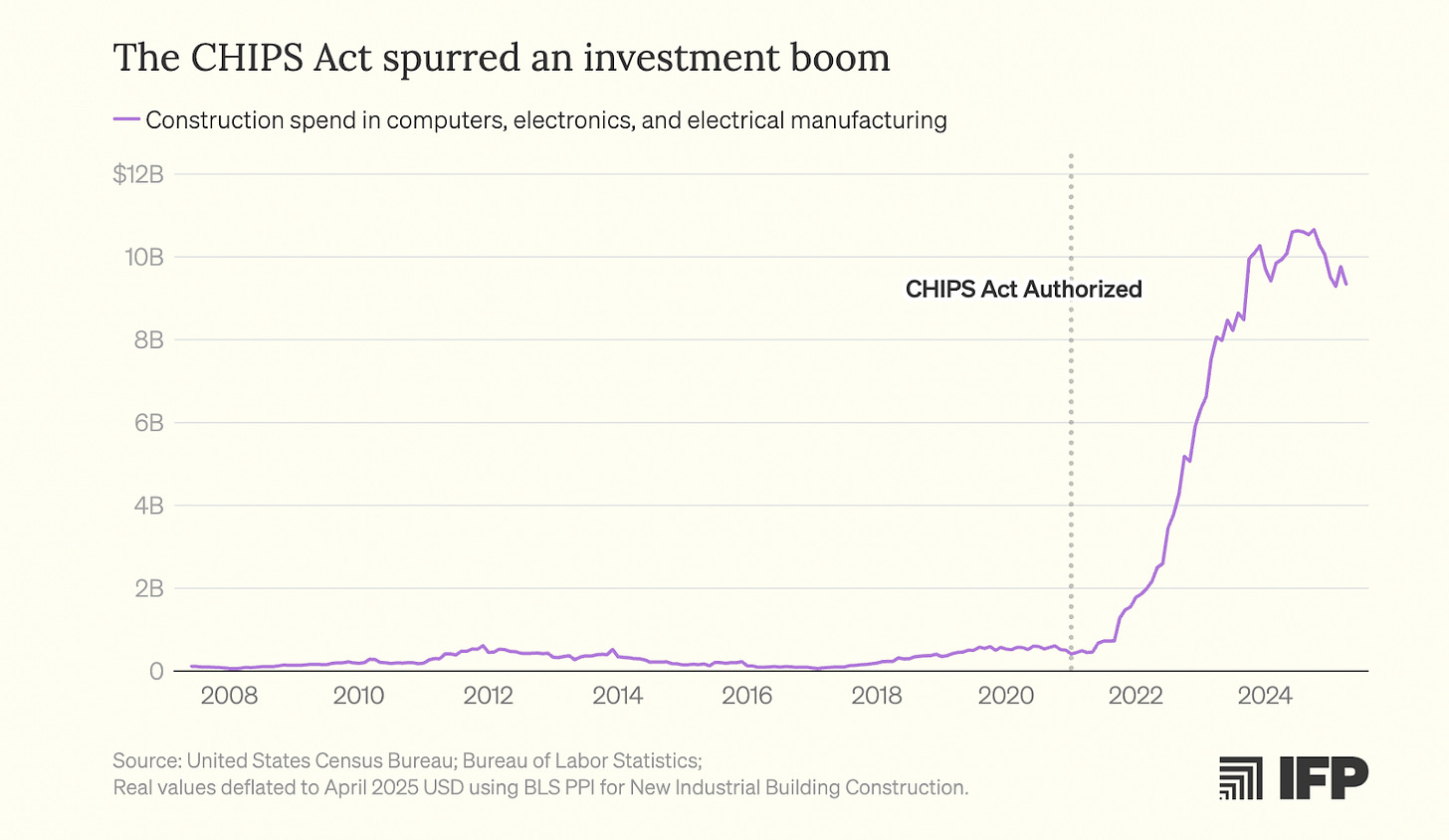

And since its enactment, the U.S. has seen a massive investment boom in semiconductor facilities. Annual construction spending on electronics manufacturing has skyrocketed – averaging nearly $72 billion per year in the last five years, almost 20 times higher than the pre-CHIPS average.

All five of the world’s leading-edge chipmakers (from Intel to TSMC) have announced major projects on U.S. soi. By late 2024, the Commerce Department’s CHIPS Program had awarded $34 billion across 20 deals, catalyzing investments that will put America back in the game for cutting-edge chips.

Critics vs. the CHIPS Team

Yet even as the CHIPS Act launched, a fierce intraparty debate erupted over how to implement it; specifically, who should be trusted to dole out all of the money.

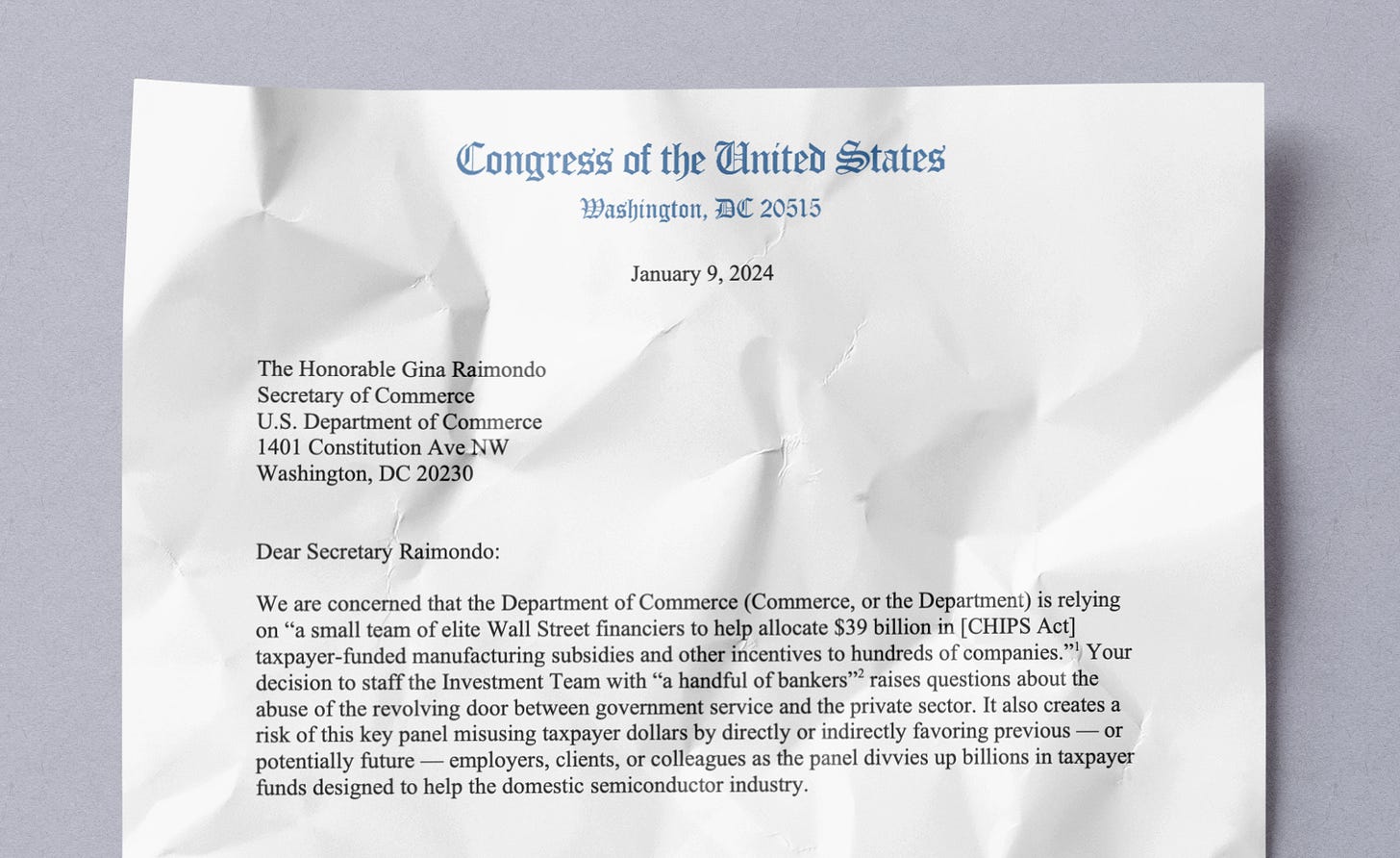

Senator Elizabeth Warren and self-styled watchdog groups sounded alarms about the personnel leading the CHIPS program. Warren (along with Rep. Pramila Jayapal) publicly blasted Commerce’s hiring of a “small team of elite Wall Street financiers” to run the CHIPS Investment Office.

In a January 2024 letter to Raimondo, they warned that staffing CHIPS with “a handful of bankers” raises “questions about the abuse of the revolving door” and the risk that ex-finance executives might favor their former firms in allocating taxpayer subsidies.

Warren rattled off the résumés of the CHIPS leadership: a former McKinsey partner, a Blackstone private equity alum, ex-Goldman Sachs and KKR executives – hardly typical bureaucrats. To Warren, this “unprecedented” influx of private-sector hires could turn a public investment program into a giveaway tailored to industry “wish-lists” rather than the public interest.

As I described in my last post, Warren’s outside allies amplified the line of attack pursued by Senator Warren. The Revolving Door Project accused Raimondo of turning the Commerce Department “into an exclusive club for Big Tech, Wall Street, and other special interests” by recruiting so many industry insiders. They even launched a dedicated “Raimondo Watch” website cataloguing her ties to financiers. In their telling, Raimondo “built a team of former Wall Street executives…to decide where the money would go” under CHIPS.

But two years after the successful implementation of the CHIPS Act – which even they agree succeeded in awarding the money and creating jobs – the anti-corporate watchdogs switched to criticizing the water usage and executive pay of semiconductor manufacturers. They do not bother to revisit previous claims of self-dealing and giveaways to financiers.

Why Tech Talent Made CHIPS a Success

Thankfully, the CHIPS Program Office took a different path than the Biden Administration had used in bringing in tech experts at the beginning of the Administration - one that proved crucial to the Act’s success.

Instead of playing it safe and trying to keep all of the factions of the party in line by only relying only on career staff and their existing political hires, Raimondo and her deputies built what was essentially a “$39 billion start-up in government” staffed with a mix of public servants and private-sector experts. Former CHIPS Director Mike Schmidt recalls being given an “extraordinary group” of colleagues, drawn from “across the public and private sectors,” including semiconductor experts and financial veterans.

Schmidt himself was a seasoned government operator, but his deputy Todd Fisher came from private equity, who would soon be the program’s dealmaking guru. Fisher said he “jumped at the chance to use skills from [his] long private sector career on a national security priority.” Industry folks weren’t there to feather any nests – they were there to get results for America.

Commerce staff began calling up major chip buyers—Apple, Nvidia, Qualcomm—not only to verify applicants’ projections, but to help coordinate demand, validate supply chains, and build a credible U.S. chip ecosystem. This proactive posture turned the CHIPS office into an information clearinghouse—and helped it spot bad fits early and focus public dollars on viable, high-impact projects.

This level of engagement, and the expertise to correctly analyze what they were hearing and act on it simply would not have been possible without the experts brought into the program from industry. The industry experts Commerce brought in knew what to ask the companies in granular detail, and they had the contacts to get the right information.

Bringing experts into government service was key to ensuring that they were subject to ethics rules, and their industry knowledge could be used to ensure that the information coming in from companies was unbiased and comprehensive; and helped the government be smart enough to make the right calls.

This iterative model wasn’t risk-free. Not every applicant received identical face time (an impossible bar under any circumstances). Critics griped about transparency even as the Administration worked diligently to make the award process as transparent as possible. But those process risks were dwarfed by the strategic risk of failure.

Companies competed not just on capital investment, but on workforce training, R&D, and national security contributions. The result: a more rigorous and transparent system that avoided insider favoritism and built a portfolio of geographically and technologically diverse investments. In short, CHIPS implementation married private-sector agility with public-sector accountability—a rare balance.

Talent and Results Over Pressure Politics

The CHIPS Act experience makes a compelling case that hiring top tech talent was worth weathering the political attacks. Senator Warren and other critics cried foul about the optics of those they slurred as “bankers” in government, but the semiconductor experts, technology investors, and financial analysts who were hired helped produce real-world outcomes that serve progressive goals: revitalizing manufacturing, creating middle-class jobs, and securing the supply of critical technology.

In the end, results speak louder than rhetoric. These are investments that make the U.S. economy more resilient and less beholden to corporate offshoring, outcomes that all Democrats should be able to support.

More broadly, CHIPS reveals a key lesson for Democrats: tech industry expertise in government is a feature, not a bug. As I argued previously, the Biden Administration’s aversion to tech-sector hires backfired, leaving it “slower and less capable” on tech challenges while still drawing fire for any minor industry link. The CHIPS program was a notable exception: it welcomed seasoned insiders (under strict ethics rules) and empowered them to drive a signature Biden initiative, and it succeeded.